Nicholas J Hudson (2011). Musical beauty and information compression: Complex to the ear but simple to the mind? BioMed Central : 10.1186/1756-0500-4-9

Edit: When I originally posted this my words were unjustifiably harsh. I have since toned down the sarcasm.

One of my favorite resources, ScienceDaily, published a brief article (Creating Simplicity: How Music Fools the Ear (I find this misleading, as the research referenced is not about trickery)) about a recently published paper in BioMed Central. It's so brief that I'm going to try something new and reproduce the article with my comments added in red.

What makes music beautiful (I know this is picky, but I'm getting kind of tired of that hook)? The best compositions transcend culture and time (I really hope that those terms get defined) -- but what is the commonality which underscores their appeal?The paper in question is Nicholas J Hudson's Musical Beauty and Information Compression: Complex to the Ear but Simple to the Mind? [HTML] [PDF]. I quickly became pessimistic while reading this paper (which was fueled by the mountain of skepticism I brought with me from the ScienceDaily article). It's full of subjective terminology and lacking in citations of claims. I began planning on tearing into this research and noticed two things. First, Dr. Nick Hudson is a doctor of muscle physiology and works with livestock. I guess the audio compression and music studies are a hobby of his, so I almost felt bad for getting mad at him. Second, I was approaching the paper with the incorrect assumption that this was about experimental research, when in fact the Article Type is "Hypothesis." I was unjustifiably primed to launch into heavy-handed criticism of a different kind of paper.

New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal BMC Research Notes suggests that the brain simplifies complex patterns, much in the same way that 'lossless' music compression formats reduce audio files, by removing redundant data and identifying patterns.

There is a long held theory that the subconscious mind can recognise patterns within complex data and that we are hardwired to find simple patterns pleasurable. Dr Nicholas Hudson used 'lossless' music compression programs to mimic the brain's ability to condense audio information. He compared the amount of compressibility of random noise to a wide range of music including classical, techno, rock, and pop, and found that, while random noise could only be compressed to 86% of its original file size, and techno, rock, and pop to about 60%, the apparently complex Beethoven's 3rd Symphony compressed to 40% (I really hope that this paper addresses the myriad of variables and subjective qualities involved in making that analogy work).

Dr Nicholas Hudson says "Enduring musical masterpieces, despite apparent complexity, possess high compressibility" and that it is this compressibility that we respond to. So whether you are a die hard classicist or a pop diva it seems that we chose the music we prefer, not by simply listening to it, but by calculating its compressibility (wait, I thought this proved that better music is more compressible — are you actually saying that people choose a compressibility ratio that they like?).

For a composer -- if you want immortality, write music which sounds complex but that, in terms of its data, is reducible to simple patterns (this concept is only new insofar as it applies to compression — it is otherwise a major and long-standing idea within the study of musical form).

Hudson's hypothesis is far from perfect, but ultimately does more good than harm. He uses too many undefined and subjective terms1, he makes claims that sprout red flags of evolutionary psychology in my mind2, and he relies overwhelmingly on one particular source as evidence for his claims3.

1"...enduring musical masterpieces" — I'll admit this is nitpicky, but every time he uses this term I want to know what qualifies as "enduring," what qualifies as a "masterpiece," and how he adjusts for the lack of opportunity for recent music to endure more than a year (he doesn't).

2"...implying that at some point in evolution...compression became linked to...reward" — Evolutionary claims about something psychological inherently need objective evidence and are inherently extremely difficult to get objective evidence for. In this case, the necessary evidence for interaction between the limbic system and whatever system "compresses" information (I suspect the hippocampus) is not cited.

3"Schmidhuber," "Schmidhuber," and "Schmidhuber" — His article presents some intriguing ideas. If Hudson had framed his work more straightforwardly as an extension of Schmidhuber's ideas, I would've been less perturbed by how constantly Schmidhuber is used as a significant source.There was good stuff, too. I must mention that almost as often as I noted a flaw in the reasoning of Hudson's primary analogy, he would later address the existence of that flaw. Hudson actually makes a number of hypotheses and ultimately proposes that people study and create experiments to test them. He tries to do a little bit of this himself, but his data is scant and not worth addressing here.

His advocacy of the idea that learning and the formation of memory is a function of compression seems worth studying. His idea that such compression may have an impact on the pleasure a listener finds in a selection would be worth studying. His argument that there is a link between cognitive compression and pleasurable reward could definitely be researched. His suggestion that "compressibility" could be a variable used in studies has merit (but would require much more significant definitions of how the variable is defined (even the type of microphone used in a recording could affect how compressible audio information could be)).

I found one part of his hypothesis particularly interesting on a philosophical level. He argues that people are extremely satisfied when a scientific law clicks in their mind (especially when they discover one), as these laws suit his model of cognitive compression quite nicely. The orbits of the planets may appear complex and completely unrelated to the fall of an apple from a tree, but once the Law of Gravity is understood, a person can compress their understanding of these things into a succinct law. He overlays that argument with a philosophy that art is, by its nature, the compression of information into a medium (an example he uses is a landscape being compressed by a painter into a painting) and subsequent decompression by a beholder (the viewer sees the painting and can decompress it to imagine the landscape). Hudson, however, never addresses the fact that the audio compression he is talking about would be an act of compression that follows decompression that follows compression — we start to get pretty far afield when we look at it this way, and it becomes more vague which point of that process has the greatest affect on how pleasurable the art is to whoever is experiencing it.

In conclusion, Hudson seems inexperienced in this field but well intentioned and philosophically creative. Study of his hypotheses could be beneficial, but may be a ways off.

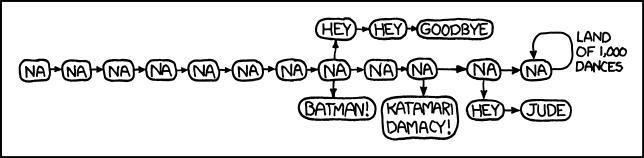

Randall Munroe has provided us with a beautiful example of conceptual compression:

|

| Music Humor From www.xkcd.com |

I have said earlier something abt one of your articles. Reading more of them I must say that your blog is nicely done and well informed. Now it's on my favourites. Good luck.

ReplyDeletePedro

Thanks!

ReplyDelete